“… according to Nwanze, the Nigeria analyst, the tensions are likely to come to a head. Nigeria’s population is continuing to mushroom—the U.N. estimates that, by 2050, Nigeria will overtake the United States as the third most populous country in the world—and its economy is sluggish, with poverty widespread. If improperly managed, the current tensions are a huge threat. Nigeria is currently unstable, and a spark could ignite a flame, he says. In its current state, and with current revenue trends, Nigeria has two decades maximum before it implodes.”

Nigeria is under threat. The West African country has the biggest population and second-largest economy on the continent. It is also one of the most ethnically diverse countries in Africa.

The fault lines between ethnic groups have recently come to the fore. Nigeria’s acting president, Yemi Osinbajo, last year fought back to keep things a little stable in the wake of an inflammatory expulsion order served by a coalition of activist groups in northern Nigeria. The so-called Northern Youth Groups demanded that all members of the Igbo —one of Nigeria’s main ethnic groups—leave northern Nigeria within three months or face forced expulsion.

Remember that Nigeria recently commemorating the 50th anniversary of a deadly war sparked by inter-ethnic tensions—hence, such statements evoke horrendous memories. They can also feed into separatist ideologies that call for the breakup of a country that only came into existence in its current form a century ago.

When did Nigeria become one country?

Nigeria has existed in its present form since the early 20th century when the British amalgamated its northern and southern protectorates in 1914 to form a single country. Unification brought together a wide variety of ethnic groups; Nigeria is home to more than 200 ethnicities and tribes. The three main ethnic groups—Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba and Igbo—are concentrated in the north, west, and southeast of the country respectively.

Nigeria spent another 46 years under British rule before gaining its independence in 1960. Its first prime minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, was a Hausa from the north. Balewa was killed in a military coup in 1966, predominantly led by Igbo officers. It was the first of many coups and power grabs that have blighted Nigeria’s history: the country did not witness a peaceful transfer of power for a long time to come..

Have people tried to break it up before?

Yes. Following the 1966 coup, waves of Igbo persecution took place across northern Nigeria, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths. Many Igbos living elsewhere in Nigeria fled to the east, and after the then-president Yakubu Gowon divided Nigeria into twelve states in 1967—a move that adversely affected the Igbo’s economic prospects—the moment for secession arrived.

An ex-Nigerian military officer, Odumegwu Ojukwu, declared the independence of a region known as Biafra on May 30, 1967. Britain backed Nigeria’s sovereignty, France supported the secessionists, and the United States remained neutral, although President Richard Nixon later accused Nigeria of genocide against the majority Igbo population in Biafra.

Ojukwu’s declaration was met with a blockade by Nigeria of Biafra’s borders and a bloody three-year civil war. At least 1 million people died, many as a result of starvation as Biafra was deprived of essential supplies. After three years of attritional warfare against the far stronger Nigerian military, the Biafrans capitulated in 1970, and the republic was reintegrated into Nigeria.

Who wants to break up Nigeria now?

Several secessionist movements are gaining traction in Nigeria at present. Firstly, recent years have witnessed a revival in pro-Biafra sentiment. This has largely been triggered by Nnamdi Kanu, a British-Nigerian who heads up the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), a group calling for secession. Kanu was arrested in Nigeria in October 2015 and charged with treasonable felony; he was bailed in May after almost two years in detention without trial.

Until recently support for an independent Biafra was on the rise: surveys by Nigerian think tank SBM Intelligence have witnessed support growing from 21.4 percent to 43.2 percent in the south and southeast over 18 months. “One thing that the pro-Biafra movement has successfully done is put the issues on the table,” says Cheta Nwanze, head of research at SBM Intelligence. But Nwanze says that autonomy, rather than full secession, is the more likely solution.

The oil-rich Niger Delta has been the site of militant insurgencies in recent years. In 2016, attacks on oil pipelines and facilities, led by a group called the Niger Delta Avengers (NDA), slashed production by more than half and drove Nigeria’s oil-dependent economy into recession. The NDA, like other Delta-based groups, have called for a greater share in Nigeria’s natural resources, but have also threatened secession, though their campaign has died down in recent months.

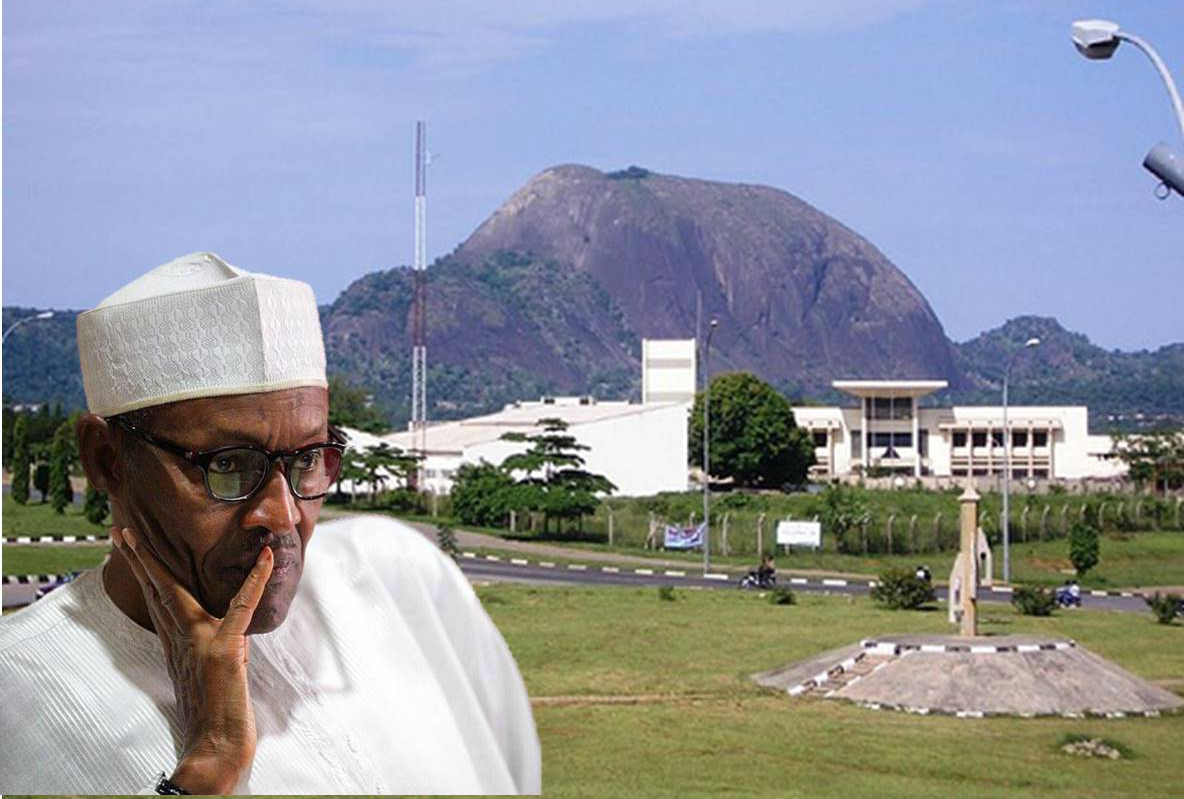

In the northeast, Boko Haram—a militant group whose name means “Western education is forbidden”—declared war on the Nigerian government in 2009 with the stated aim of establishing a radical Islamist caliphate in the region. At its strongest point in early 2015, Boko Haram controlled territory equivalent to the size of Belgium. But since Buhari came to power, it has been beaten back and much of its territory reclaimed by government forces. The group remains a menace, however, and has launched some 60 attacks since 2017.

How is the government dealing with it?

The Buhari administration has been successful at taking back territory from Boko Haram, even while the jihadis continue to carry out suicide bombings. And after stoking more tension by sending the military into the Niger Delta, the government has managed to calm tensions, in part by extending amnesty payments to former militants in the region.

On the Biafra issue, however, the government’s response has been widely criticized as heavy-handed. Amnesty International said that Nigeria’s military had employed a “reckless and trigger-happy approach” in dealing with pro-Biafra protests, killing 150 demonstrators since August 2015 ; the military denied it had used undue force.

Max Siollun, a historian of Nigeria, believes that the government is unlikely to give in to the secessionist’s demands, particularly given the bloodshed of the 1967 war. “There is very little chance of the federal government considering an independence referendum for any part of Nigeria,” says Siollun, the author of Soldiers of Fortune: A History of Nigeria (1983-1993) . “Nigeria’s elites will handle these secessionist demands the way they always do: via some form of unwieldy yet ingenious backdoor compromise.”

What’s going to happen next?

In the wake of the divisive statement made by the Northern Youth Groups, Vice-President Osinbajo met with governors and traditional rulers from both the north and the southeast. The Nigerian government has been quick to emphasize the country’s indissoluble unity, and Osinbajo has threatened that ethnic inciters will face the “full force of the law.”

But according to Nwanze, the Nigeria analyst, the tensions are likely to come to a head. Nigeria’s population is continuing to mushroom—the U.N. estimates that, by 2050, Nigeria will overtake the United States as the third most populous country in the world—and its economy is sluggish, with poverty widespread. “If improperly managed, the current tensions are a huge threat. Nigeria is currently unstable, and a spark could ignite a flame,” says Nwanze. “In its current state, and with current revenue trends, Nigeria has two decades maximum before it implodes.”

This article was originally published with the title: Why is Nigeria One Country and Who Wants to Divide It?